Documentary maker Lucy Winer has produced an amazing story of her own history and her journey of discovery when returning back to the Asylum that she once called a temporary home. The following is a review I wrote for Florish Newsletter.

Documentary maker Lucy Winer has produced an amazing story of her own history and her journey of discovery when returning back to the Asylum that she once called a temporary home. The following is a review I wrote for Florish Newsletter.

Only last week I heard this phrase by Morgan Freeman as the character Red in the film Shawshank Redemption, “These walls are funny. First you hate ’em, then you get used to ’em. Enough time passes, you get so you depend on them. That’s institutionalized.” I had to find the quote later on the internet because this helped me sum up the documentary that I had just watched called “Kings Park, stories from an American Mental Institution”. Most documentaries about Mental Health facilities are written by ex-staff or historians who have either one perspective or no lived experience and are often taken as an accurate record of events. This film is very different because it tells the story from the an insider’s perspective, Lucy Winer was a Patient at Kings Park Hospital at the early age of 17 years, back in June 1967, diagnosed with severe depression she made a number of failed attempts to take her own life before being admitted.

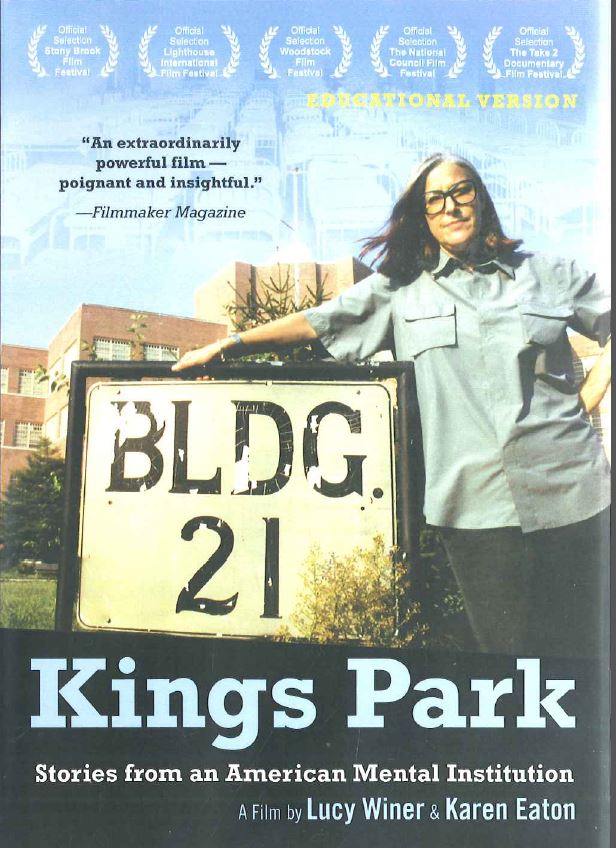

The film is broken down into three parts; the first is Lu-cy’s own story and her return to the rooms of Ward 210, the female violent ward of Building 21. It is a deeply per-sonal journey which is well articulated through Lucy’s commentary. The strain of facing her history and the past helped her but also created more questions than it did answers. Lucy explains some of the scenes she witnessed and was involved in while also attempting to hold onto her own feelings of being confronted by the peeling walls and deep memories of past treatment practices in

a decaying old building that ruled over her life during the late 60’s and has stayed with her up until her 50th birthday.

While this was the first part of the film and the only part that was originally planned, the questions that she was left with needed answers. So parts two and three took on a life and explored the history of the hospital and its context within a community. Like all of these institutions, people’s memories are extremely varied, some memories stay vivid and others fade over time while the different perspectives are confronted and examined as Lucy meets the old former staff, her first Psychiatrist, the town’s people and fellow ex-patients.

Some people just couldn’t face their past, like the torment and abuse that they had been subjected to many years ago, there present disallowed and controlled even walking toward the old buildings, while others took heart that they could swing the wrecking ball to destroy their own past experiences and suffering by physically knocking down the walls. Ex-staff admitted that they often didn’t know what they were doing and were over-whelmed by the enormity of the job in front of them. Many remember the life of close friendships with other staff and the life lived around one of the largest employers in the area.

The third part explores the deinstitutionalisation programs and shared living arrangements that were set up during that phase. Lucy again explores Mental Health Services and the slow decline of facilities and services to those with a mental health condition. She visits the last place people arrive at once they fall between the cracks of a poor system of care, the State Prison Services are now considered to be one of America’s leading Mental Health Care Providers.

All through watching this well made, professionally produced and edited film I realised that the institutional language that Lucy was talking about in America is the same in just about every western country in the world that went down the path of segregation and isolation. The same institutional behaviours that governed the patients also imprisoned the staff, even the local town’s folk. Kings Park isn’t unsimular to any institutional story I’ve heard before except for the fact that this is one of the limited stories told from a patient’s view, a patient that is willing and able to confront her past mental health, her treatment, her past clinical staff and look toward the future. She wants her film to challenge and agitate debate about the future of mental health services. The power of this film lies in the connections it draws between the hopes and failures of the past and the challenges of the present.

It is easy to take a person out of an institution but it is not so easy to take the institution out of the person.

The DVD is available in Standard Definition and Blu-ray; it’s also available as an educational version and comes with a range of teaching materials. The cost is $30 US dollars plus postage of $25 US dollars, which is about $71 AU dollars for the SD version. There is an online version available. As the Moderator of the Willow Court History Group I have approached Lucy and we are discussing a cheaper way to view or purchase this film in Australia. Information will be posted on my website once Australian distribution rights and permission to screen the film are granted.

Mark Krause